General Statistics

- Nearly 1 in 3 students (27.8%) report being bullied during the school year (National Center for Educational Statistics, 2013).

- 64 percent of children who were bullied did not report it; only 36 percent reported the bullying(Petrosina, Guckenburg, DeVoe, and Hanson, 2010).

- More than half of bullying situations (57 percent) stop when a peer intervenes on behalf of the student being bullied (Hawkins, Pepler, and Craig, 2001).

- School-based bullying prevention programs decrease bullying by up to 25% (McCallion and Feder, 2013).

- The reasons for being bullied reported most often by students were looks (55%), body shape (37%), and race (16%) (Davis and Nixon, 2010).

Effects of Bullying

- Students who experience bullying are at increased risk for depression, anxiety, sleep difficulties, and poor school adjustment (Center for Disease Control, 2012).

- Students who bully others are at increased risk for substance use, academic problems, and violence later in adolescence and adulthood (Center for Disease Control, 2012).

- Compared to students who only bully, or who are only victims, students who do both suffer the most serious consequences and are at greater risk for both mental health and behavior problems (Center for Disease Control, 2012).

- Students who experience bullying are twice as likely as non-bullied peers to experience negative health effects such as headaches and stomachaches (Gini and Pozzoli, 2013)

Statistics about bullying of students with disabilities

- Only 10 U.S. studies have been conducted on the connection between bullying and developmental disabilities, but all of these studies found that children with disabilities were two to three times more likely to be bullied than their nondisabled peers. (Marshall, Kendall, Banks & Gover (Eds.), 2009).

- Researchers discovered that students with disabilities were more worried about school safety and being injured or harassed by other peers compared to students without a disability (Saylor & Leach, 2009).

- The National Autistic Society reports that 40 percent of children with autism and 60 percent of children with Asperger’s syndrome have experienced bullying.

- When reporting bullying youth in special education were told not to tattle almost twice as often as youth not in special education (Davis and Nixon, 2010).

Statistics about bullying of students of color

- More than one third of adolescents reporting bullying report bias-based school bullying (Russell, Sinclair, Poteat, and Koenig, 2012).

- Bias-based bullying is more strongly associated with compromised health than general bullying (Russell, Sinclair, Poteat, and Koenig, 2012).

- Race-related bullying is significantly associated with negative emotional and physical health effects (Rosenthal et al, 2013)

Statistics about bullying of students who identify or are perceived as LGBTQ

- 81.9% of students who identify as LGBTQ were bullied in the last year based on their sexual orientation (National School Climate Survey, 2011).

- Peer victimization of all youth was less likely to occur in schools with bullying policies that are inclusive of LGBTQ students (Hatzenbuehler and Keyes, 2012).

- 63.5% of students feel unsafe because of their sexual orientation, and 43.9% because of their gender expression (National School Climate Survey, 2011).

- 31.8% of LGBTQ students missed at least one entire day of school in the past month because they felt unsafe or uncomfortable (National School Climate Survey, 2011).

Weight-Based Bullying

- 64% of students enrolled in weight-loss programs reported experiencing weight-based victimization (Puhl, Peterson, and Luedicke, 2012).

- One third of girls and one fourth of boys report weight-based teasing from peers, but prevalence rates increase to approximately 60% among the heaviest students (Puhl, Luedicke, and Heuer, 2011).

- 84% of students observed students perceived as overweight being called names or getting teased during physical activities (Puhl, Luedicke, and Heuer, 2011).

Bullying and Suicide

- There is a strong association between bullying and suicide-related behaviors, but this relationships is often mediated by other factors, including depression and delinquency (Hertz, Donato, and Wright, 2013).

- Youth victimized by their peers were 2.4 times more likely to report suicidal ideation and 3.3 times more likely to report a suicide attempt than youth who reported not being bullied (Espelage and Holt, 2013).

- Students who are both bullied and engage in bullying behavior are the highest risk group for adverse outcomes (Espelage and Holt, 2013).

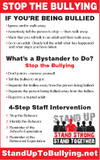

Interventions

- Bullied youth were most likely to report that actions that accessed support from others made a positive difference (Davis and Nixon, 2010).

- Actions aimed at changing the behavior of the bullying youth (fighting, getting back at them, telling them to stop, etc.) were rated as more likely to make things worse (Davis and Nixon, 2010).

- Students reported that the most helpful things teachers can do are: listen to the student, check in with them afterwards to see if the bullying stopped, and give the student advice (Davis and Nixon, 2010).

- Students reported that the most harmful things teachers can do are: tell the student to solve the problem themselves, tell the student that the bullying wouldn’t happen if they acted differently, ignored what was going on, or tell the student to stop tattling (Davis and Nixon, 2010).

- As reported by students who have been bullied, the self-actions that had some of the most negative impacts (telling the person to stop/how I feel, walking away, pretending it doesn’t bother me) are often used by youth and often recommended to youth (Davis and Nixon, 2010).

Bystanders

- Bystanders’ beliefs in their social self-efficacy were positively associated with defending behavior and negatively associated with passive behavior from bystanders – i.e. if students believe they can make a difference, they’re more likely to act (Thornberg et al, 2012)

- Students who experience bullying report that allying and supportive actions from their peers (such as spending time with the student, talking to him/her, helping him/her get away, or giving advice) were the most helpful actions from bystanders (Davis and Nixon, 2010).

- Students who experience bullying are more likely to find peer actions helpful than educator or self-actions (Davis and Nixon, 2010).

References:

Bullying: A guide for parents. (National Autistic Society). Retrieved from http://www.autism.org.uk/Living-with-autism/Education-and-transition/Primary-and-secondary-school/Your-child-at-school/Bullying-a-guide-for-parents.aspx

Center for Disease Control, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (2012). Understanding bullying.

Davis, S., & Nixon, C. (2010). The youth voice research project: Victimization and strategies.

Espelage, D. L., & Holt, M. K. (2013). Suicidal ideation and school bullying experiences after controlling for depression and delinquency. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53.

Gini, G., & Pozzoli, T. (2013). Bullied children and psychosomatic problems: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics.

Hatzenbuehler, M. L., & Keyes, K. M. (2012). Inclusive anti-bullying policies and reduced risk of suicide attempts in lesbian and gay youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53, 21-26.

Hawkins, D. L., Pepler, D. J., & Craig, W. M. (2001). Naturalistic observations of peer interventions in bullying. Social Development, 10(4), 512-527.

Hertz, M. F., Donato, I., & Wright, J. (2013). Bullying and suicide: A public health approach. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53.

Kosciw, J. G., Greytak, E. A., Bartkiewicz, M. J., Boesen, M. J., & Palmer, N. A. GLSEN, (2011). The 2011 national school climate survey. Retrieved from website: http://glsen.org/sites/default/files/2011 National School Climate Survey Full Report.pdf.

(2009). C. Marshall, E. Kendall, M. Banks & R. Gover (Eds.), Disabilities: Insights from across fields and around the world (Vol. 1-3). Westport, CT: Praeger Perspectives.

McCallion, G., & Feder, J. (2013). Student bullying: Overview of research, federal initiatives, and legal issues. Congressional Research Service.

Petrosino, A., Guckenburg, S., DeVoe, J., & Hanson, T. Institute of Education Sciences, (2010). What characteristics of bullying, bullying victims, and schools are associated with increased reporting of bullying to school officials? Washington, D.C.: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance.

Puhl, R. M., Luedicke, J., & Heuer, C. (2011). Weight-based victimization toward overweight adolescents: Observations and reactions of peers. Journal of School Health, 81(11), 696-703.

Puhl, R. M., Peterson, J. L., & Luedicke, J. (2012). Strategies to address weight-based victimization: Youths' preferred support interventions from classmates, teachers, and parents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(3), 315-327.

Rosenthal, L., Earnshaw, V. A., Carroll-Scott, A., Henderson, K. E., Peters, S. M., McCaslin, C., & Ickovics, J. R. (2013). Weight- and race-based bulling: Health associations among urban adolescents. Journal of Health Psychology.

Russell, S. T., Sinclair, K., Poteat, P., & Koenig, B. (2012). Adolescent health and harassment based on discriminatory bias. American Journal of Public Health, 102(3), 493-495.

Saylor, C.F. & Leach, J.B. (2009) Perceived bullying and social support students accessing special inclusion programming. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities. 21, 69-80.

Thornberg, T., Tenenbaum, L., Varjas, K., Meyers, J., Jungert, T., & Vanegas, G. (2012). Bystander motivation in bullying incidents: To intervene or not to intervene? Western Journal of Emergency Medicine , 8(3), 247-252.

U.S. Department of Education , National Center for Educational Statistics (2013). Student reports of bullying and cyber-bullying: Results from the 2011 school crime supplement to the national crime victimization survey.

Wright, T., & Smith, N. (2013). Bullying of LGBT youth and school climate for LGBT educators. GEMS (Gender, Education, Music, & Society, 6(1).

|

|

|